It is best not to let your IQ yield to the EQ. After all, none of us are in absolute control of ours or for that matter others’ lives and neither was it meant to be, writes Nagesh Alai

Navin Vora (name changed), aged 85, an automobile engineer did exceedingly well in his corporate life, was married to a lovely homemaker, and had brought up his two children with care and world class education. He retired about a score ago and was leading a happy retired life with his wife in his airy apartment and feeling proud about his children. His son is a top-echelon executive in a well-known technology company and is doing exceedingly well, thanks to his high education and competence. His daughter is married and well settled. Everything was going fine till his wife’s sudden death earlier this year. After a brief stay with his son, today, he is lodged in an old age home, bereft of the companionship of his late wife and any feelings of his children. Navin Vora is in decent health, but would never have imagined that he would find himself in this situation. Extremely gregarious and witty, full of zest for life, he is desolate today and a shadow of his former self.

Mr and Mrs Srivastava (name changed), in their 80s, have their children settled abroad. Mr Srivastava is of good health, but Mrs Srivastava is dependent and wheelchair bound. A practical man of wisdom and experience, he chose to move to an assisted old age home down south in Kovai (Coimbatore). The community complex provides for all possible assistance and medical care that the aged may need and an ecosystem of healthy eating and group activities.

Mrs Sreedevi Chandran (name changed), a widow aged 86, lives all alone in a distant suburb. Both her children live abroad, busy in their respective calling. Her children stay in touch with her regularly and order her daily needs on Amazon (talk of beneficent technology) and try their best to ensure her comfort. She has a set of good neighbours (god bless them) who are supportive and keep a check on her.

Another known person gave away all his wealth and home in advance to his children, thinking that they will take care of him. Unfortunately, to cut a long story short, he is finding himself homeless today and fighting a court case to retrieve his home for some semblance of decent living. The once-high-flyer billionaire, Vijaypat Singhania, is not the only sufferer.

Two weeks ago, a person settled abroad, reached out to a friend to find some caregiver to take care of his aged parents. He expressed practical difficulties in getting his parents over to stay with him and helplessness.

Stories, such as above, are real and abound and span cities, communities and classes. Little wonder that an act, Maintenance and Welfare of Parents and Senior Citizens Act, 2007 was enacted. The act obliges children to maintain their parents/grandparents and to protect the life and property of such persons. The act also provides for setting up of old age homes for providing maintenance to penurious parents and senior citizens. It is a travesty that such an act had to be promulgated in a society like ours, where historically and culturally, care of the old has been held as a filial responsibility and not an obligation.

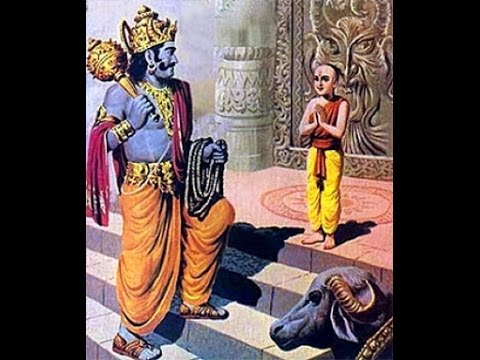

Let’s take a look at the Kathopanishad, an ancient Samhita (text or verses). It is essentially the story of an interlude between a child, Nachiketa and Yama. Performing yajna or sacrifice was an important religious practice in Vedic times. Nachiketa once saw his father, King Vajashravas, giving away his old and feeble cattle, which would not have been of any use to the donees. Nachiketa pointed this out to his father and said that it will be better if he himself is offered as charity, rather than unproductive cows. The annoyed king retorts that he will give him away to death instead. An inquisitive Nachiketa, wishing to meet death, sets out in search of Yama. Seeing the trials and tribulations that the child is going through in his search and impressed with his determination, Yama presents himself before Nachiketa and grants him three boons of his choice. The story goes on to say that Nachiketa asks for (1) bestowal of a good relationship with his father, (2) that his father be taught the right way of sacrifice and (3) the revelation of the secret of death. Yama willingly gives Nachiketa the first two boons, but is hesitant to give him the third boon, given the subject. But an unrelenting Nachiketa, persuades Yama to share with him the meaning of life and death. Yama goes on to explain the difference between paramatman (the supreme being or consciousness), the atman (self or soul) and the body (a mere carrier or a vestige) and that the purpose of life is to realise that the atman is but a microcosm of the paramatman and moksha is achieved on the realisation of the Self. Moksha means to get a release from the cycle of birth and death.

Clearly, the child in Nachiketa understands the need for love and care towards his father, regardless of anything and asks for that boon and in the process gets an insightful exposition on birth and death.

Unfortunately, behavioural changes in humankind and structural alterations in culture and society are inevitable consequences of progress. The selflessness of a wholesome past will yield to the want and wanton times of the present, creating conflicts of situations and emotions and impacting relationships themselves.

If in the western world, leaving the parental homes and fending for oneself from the age of 18 is a generally accepted norm, it will not be before long before it permeates the Indian society as well, especially in urban areas, if it has not already. If the urban kids are migrating early on to overseas shores for higher education and better lives, the rural youths are now migrating in hordes to urban areas for the same reasons. Whether urban or rural, the impact is on the aged, who are willy-nilly left to fend for themselves and manage as well as possible. It is not that children are irresponsible towards their parents. Many are caring and loving and do not dump their parents, thanks to the enduring Indian model of all-round self-development and emphasis on caring for the ageing members of the family. They try and do everything possible to tend to them and give them a physical and psychological sense of belonging. They use technology as best as possible to stay connected and provide the comforts.

The mushrooming old age homes and assisted living coming up in many cities and towns, NGOs providing care and comity to senior citizens, governmental measures in the form of some social security schemes and laws, citizens groups, app based help portals, etc., are signs of a recognition of the problem of elder care, abuse and destitution and provide some succour, if not a complete cure. Building awareness and sensitizing the citizenry with the right messaging about the need to take care of parents and senior citizens is a regular initiative of states and corporates alike. Hopefully, these will bring about a change in mindsets towards elders and elder care.

As for those in migration to the silver years and hoping for a continued well-being, they will do well to follow Shushruta’s advise of swasthya (good health), dinacharya (following daily routines), riturcharya (following climatic/seasonal routines), regular exercises and moderation in diet. Equanimity and mental health could be aided through spiritual routines like meditation and contemplation. Going back to our roots is the only way we can cope with the reality and adversity of life. Attachment is good, but detachment is practical. It is best not to let your IQ yield to EQ. After all, none of us are in absolute control of ours or for that matter others’ lives and neither was it meant to be.

Closer home, a few years ago, a relative, after much discussions and advocacy of a joint family with his children, planned out a consolidation of his finances to set up a larger roof. Since then, one of his children has already moved to a different city and the other is soon planning to fly off to a different destination. Though both deeply care for and love their parents, they had to make a choice and they did. That’s the law of nature; if you have wings, you will fly. Those who cannot, it is best to roost and not rue. After all, life is an array of choices and living is an array of decisions. The relative is back to the drawing board.

As for Navin Vora, I am hoping that he will come to terms and accept his reality, and yet live the remainder of his life to the fullest. Atharva Veda says, ‘pashyema sharadaha shatam, jivet sharadaha shatam’ (let me see 100 autumns, let me live 100 autumns). He came crying, let him go laughing, a great wit that he is.

This article is in arrangement with seniorstoday.in